HELMETS

- strie4

- Jan 5

- 8 min read

“Where’s your helmet, Grandad?”

That was the rudest thing that was ever said to me on a cricket field. It was, I think, the last time I played in a match. I had come to the conclusion it was high time to put away my bat for good. Though not yet in my dotage, notwithstanding the reference to being a grandad (many years away from that landmark), I just felt unable to step down a level from professional to club cricket and frankly wasn’t enjoying it anymore.

I had come to the crease helmetless. Although helmets had by now become an essential component of every cricketer’s kitbag, I did not possess one and thought that at this level it would be superfluous. No club bowler was ever going to threaten my cranium. Many people do not appreciate the vast difference between the professional and the recreational game. The difference can be put into context quite simply. Club cricket is played with the ball bouncing no higher than waist level. In the professional game, the ball is played predominantly between waist and head height. Hence my utter

scorn for the crass comment by the bowler as he greeted my arrival at the wicket. He was never going to intimidate me. I was quite pleased with my riposte, however.

“My helmet? Why, where it always is. On the end of my knob! Where’s yours?”

Normally, ‘sledging’ per se never concerned me (in our day in county cricket, no such thing existed; we were all professionals and respected each other and the game), but my response had slipped out almost inadvertently. At least the slips were amused.

But this piece is about helmets, not about sledging. Helmets did not appear on the scene until after I had retired. Their introduction came about, as did so many new initiatives, during the Packer Revolution and the advent of World Series Cricket between 1977-79. Andy Roberts (West Indies) with a wicked bouncer had just smashed the jaw of David Hookes (Australia), who was the poster boy of the Australian team and the whole Packer Circus. “If I put you in a crash helmet,” Packer asked Hookes, “will you go out there and carry on batting?” Of course, he was asking the impossible, but the idea had been floated, designers and technicians set to work, several prototypes were produced and The game of cricket was never the same again.

Would I have worn a helmet had they been available when I was playing? Is the Pope a Catholic, has always been my response. The only player who abjured their use was Viv Richards and none of us was a Viv Richards. He liked to announce his utter invincibility to all and sundry when he came to the wicket. I wear my maroon West Indies cap, he seemed to be saying – try to knock it off if you dare. Some tried, but the ball invariably sailed into the stands.

Nor do I for one moment bemoan their introduction as ugly, functional and impersonal, though, like many spectators, I love it when the spinners are on and the batsmen – well, some of them – remove their helmets to don the cap of their club or country. All at once, they become more recognisable for a brief moment when the game returns to an altogether gentler age. No, helmets are here to stay and have saved countless batsmen from serious injury.

But that is my point…. “countless batsmen”. In just about every game of cricket I watch, in the flesh or on the television, somebody is ‘sweded’, to use the word for getting hit on the head that was commonplace back in the day (no idea why, nothing to do with the country or the vegetable, as far as I know). The simple fact is that Accident and Emergency Units in hospitals up and down the country would have been full to overflowing had it not been for the helmet. How come? Why are players getting hit on the helmet so frequently today when batsmen before their introduction were not (very often, at any rate)?

I am entering the field of conjecture here, never having worn one myself, but do helmets give the batsman a false sense of security? In much the same way as driving in a car. You feel safe and secure but cold logic says you are travelling at high speed in nothing much more than a tin can that can be ripped apart and splintered in a torn jumble of twisted metal in the blink of an eye. Thus, batsmen today are more inclined to go after the short ball. The risk of serious injury has diminished and that square leg boundary looks awfully inviting. Pre-helmet, the short ball was one to avoid in any manner possible, sometimes in an ungainly twist and turn of the body. Unless you were an accomplished hooker and had been in long enough to assess the pace and the bounce of the wicket and had taken on this bowler before and come out on top. Otherwise, discretion played the better part of valour, and you ducked and weaved until the nasty fast bowler was replaced.

It has been calculated that a batsman facing a delivery of 90mph has 0.4 of a second to react. In effect that means no time at all. Any aggressive shot played at a 90mph delivery is therefore premeditated. The batsman has weighed up the risk benefit of such a shot and decided, if the ball is short, that he will hook or pull it, regardless of whether there is a chance he will get hit. Wearing a helmet, the risk of serious injury to the face or head has been significantly reduced. As for the ramp…. No batsman in his right mind would essay such a shot if his face wasn’t protected by a grille.

The question I pose is… has the game changed as a result of helmets? I would contend that it has, at least as far as the art of batting is concerned. Though here I add a codicil.

Art and batsmanship do not these days sit comfortably alongside each other. Batting has become more aggressive, more brutal, more destructive (helped of course by thicker bats and shorter boundaries), and there is not a lot of art about it. Remember the classic cover drive of a Tom Graveney, the delicate on drive of a Colin Cowdrey, the languid clip off his legs of a David Gower? Batsmen take on the short ball much more than hitherto. There may be more sixes sailing over the ropes but there has been a falling off in how to play the short ball defensively. Batsmen still get themselves into such a technical muddle when deceived by a short ball, and as a result, they often find they are making their way back to the pavilion, at least thankfully under their own steam and not on a stretcher. The short ball and the bouncer are still a potent weapon, helmet or no helmet.

Ian Botham was a fearless hooker. Mind you, nothing ever seemed to worry him.

Butch White, Hampshire’s legendary fast bowler of the 1960s, once admitted to me that bowling fast was “bloody hard work” and to bowl a bouncer took it out of him. If a batsman swayed harmlessly out of the way of one of his wickedest bouncers, he would begin to doubt whether the extra effort was worth it, so much screwing up of muscle and sinew for no reward. Whereas if a batsman took him on, he reckoned one or two more short balls would definitely be worth it. A fraction of a second’s miscalculation and… “bingo!”. He did not elaborate whether he meant a wicket or a batsman prostrate on the crease, blood pouring from a facial wound. Somehow, I sensed he really didn’t mind which. Fast bowlers are like that.

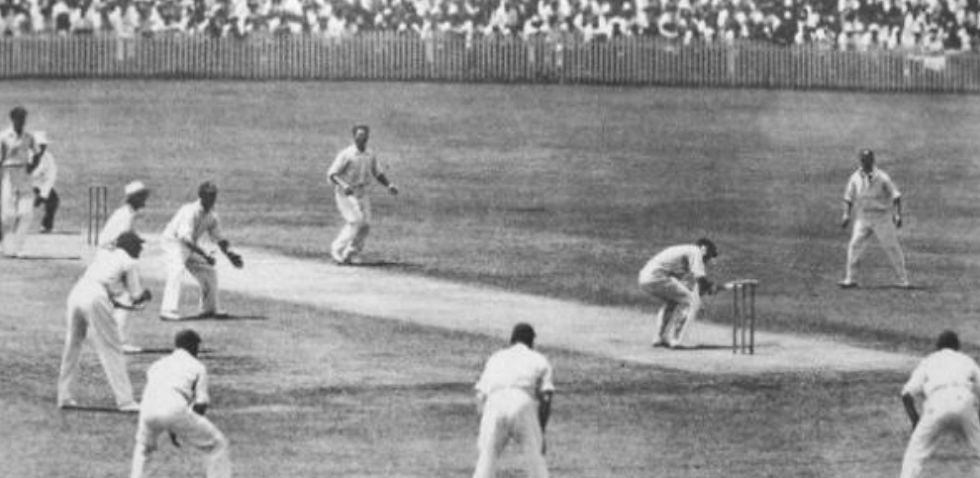

Argument over the use – and misuse – of the short ball raged most fiercely and bitterly during and after the infamous Bodyline Ashes series of 1932-33. Famously, the Australian captain, Bill Woodfull, offered this comment to the world: “There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not.” He was referring to what he, and most of Australia, thought about the English tactic of bowling fast, short-pitched balls at the body with a packed leg-side field. It was, he contended, dangerous and unsportsmanlike. It was a tactic, of course, designed to curb the run exploits of Don Bradman. You could say that it was (partly) successful. Bradman’s average for the series dropped to 56.57, as opposed to his Test career average of a smidgen under 100. Fleeting newsreel footage and photo images of the problems for the Australian batsmen facing the fastest bowler in the world, Harold Larwood, are stark and harrowing. Would Bradman have donned a helmet? You bet your dingo he would have.

I am frequently asked what it was like facing the world’s fastest bowlers – without a helmet. Bloody terrifying is my usual response. But that is not strictly true. You cannot afford to be terrified, or you would be struck immobile with fear and what you do need facing balls in excess of 90mph is to be nimble on your feet. Of course. you are anxious before you go in and wish that you didn’t have to but as sure as eggs are eggs, a wicket falls and in you go. My method was uncomplicated. I reckoned if I watched the ball carefully and trusted in my technique, then there was a good chance I would emerge unscathed. Quite simply, I stepped back and across with my eyes on a level with off stump, keeping my body sideways on thus reducing the target - in much the same way that duellists also turned sideways on - and to play the ball defensively if it was on off stump and to leave it if it was any wider. Never look back towards the wicket-keeper as he leaps to take the ball you have left alone; that will only disconcert you. The problem was that this was purely a case of survival. For the life of me, I couldn’t work out where I was going to score a run. You can’t be passive all day. Unfortunately, I cannot say that I ever took the battle to them. They may not have got me out, but I never scored many runs. That is why I so much admired batsmen who played the quicks well and prospered.

Would I have prospered wearing a helmet? I bet there were batsmen in the 18th Century who wished they could have taken advantage of leg guards when their introduction came about, rather than the rudimentary canvas/cork pads they had to wear. The game moves on as does protective equipment and we must all be thankful for that.

Comments